Industry and Background Research

Market research took place over the course of the project. Organizations with a vested interest in airborne particle surveillance were contacted, as they are the foremost prospective clients if the SLAMbot ever enters a salable stage. Airborne particle surveillance represents an unavoidable operating expense for such organizations, since without bare-minimum contamination levels they must halt production, perhaps indefinitely.

Facilities Contacted

Four organizations were contacted:

- Center for Solid State Electronics Research (CSSER) at Arizona State University (research; 17 October 2014)

- Freescale Semiconductor in Chandler (commercial; 13 November 2014)

- Ultra Clean Technology (commercial; 20 November 2014)

- ASU MacroTechnology Works (commercial; 28 January 2015)

With the exception of the CSSER and UCT facilities, all feedback was collected on-site in an interview fashion.

Of the four organizations contacted, one is a research-driven facility, while the remaining three are business-driven. A research-oriented facility is usually part of an academic organization and used for educational purposes, while a commercial facility is typically a business that manufactures products for a profit. In either case, airborne particle surveillance takes place in a cleanroom environment, where sensitive electronics are manufactured by highly trained staff. Both classes of facilities are issued industry-standard clean ratings that reflect the purity of their cleanroom environments.

The key distinction is that an educational research facility allocates far less resources (such as capital) into its cleanroom and usually has a less-impressive cleanliness rating. The commercial facility invests far more into cleanroom maintenance and air testing equipment - the quality of its products/services and the reputation of the company can often be gleamed from the cleanliness rating alone. Since they operate for-profit, commercial facilities/organizations represent a foremost client base for the SLAMbot, since they will depend far greater on reliable air testing and are capable of investing more capital.

Common concerns

The most recurring concerns or mentions were as follows: (quotes are paraphrased)

“The staff might trip over it due to its extremely small size.” The final “looks-like” prototype draft will have a chassis that is 2 feet long by 1.5 feet wide and stands 2.5 feet tall. The “looks-like” prototype will be equipped with two flashing yellow LEDs that span the length of the left and right sides of the SLAMbot. Additionally, a (non-alarming) siren will sound periodically when the SLAMbot is nearby and in surveillance mode. Together, these precautions should give ample notice to any on-site staff that the SLAMbot is in the vicinity.

“Airborne particle surveillance must not be restricted to just a few inches off the floor.” The SLAMbot chassis is fitted with an extendable/retractable vertical arm that extends 4 feet. Combined with the wheels, the chassis, the vertical arm, and the sensor itself, air testing can take place anywhere from 2’5” to 7’4” off the ground.

“The wheels and motors might generate dust on their own, making true particle detection a lost cause.” Per this feedback, the motors have been moved to within the chassis and brake/dust casing for the wheels can be ordered to make dust generation a non-issue; sealing the entire chassis in transparent polyurethane is a simple precaution.

“Any electromagnetic interference (EMI) that the electronic components might generate?” The motors and electronics can be shielded with metal to prevent EMI. Some more expensive LIDARs are shielded as well. In the final product the WiFi can be disabled while inside the cleanroom and re-enabled once testing is complete.

“Is the battery life of the SLAMbot suitable for facilities of large size?” The current “works-like” prototype of the SLAMbot is equipped with a dual-cell two 7.45V lithium ion batteries that can give at least 1.4 hours of uninterrupted use with every single component busy (a “worst-case” scenario). The lifetime is 6 hours if every component is idle (a “best-case” scenario). Although 1.4 hours of life may be sufficient for small sites such as research-based facilities, significantly larger, multi-floor commercial sites will find limited use or interest in the current model. A salable version of the SLAMbot will be fitted with a much longer-lasting battery. When the SLAMbot will not be in use for a significant period of time, it charges by docking automatically itself into a charging base.

“Will there be any impact on daily staff productivity or day-to-day operations from having the SLAMbot do air testing?” One of the key advantages of the SLAMbot as an alternative to current air testing methods is that it doesn’t require staff to operate it. A reasonable expectation is that air testing be planned into daily/weekly schedules with itineraries posted in a conspicuous manner such that relevant staff and personnel will have knowledge of the testing beforehand. This way, staff would know ahead of time to be expecting the SLAMbot to be in the room.

“Is the SLAMbot economically competitive with current air-sensing technology?” During the on-site interview with Freescale Semiconductor, the staff mentioned that one of the equipment they use, a wall-mounted air sensor, is the PMS LASAIR 110-2 (cost: $20,000; source: manufacturer e-mail). Such costs are typical of commercial facilities, and often these facilities purchase many of these sensors in addition to basic handheld sensors. The SLAMbot is designed to operate alone; that is, without the need for multiple units to sample the air throughout an entire facility.

The most expensive piece of equipment on the SLAMbot will always be the air sensor. All the other components (chassis, motors, battery, reporting software) together don’t even come close to the cost of the sensor itself, so they can be considered “fixed costs.” True to its modular conception, consumers will have the option of outfitting their own personal SLAMbot with an air sensor suitable to the needs of their facility, where “needs” describes the sensor that will be able to award them their desired cleanliness rating. (A cheap sensor with a very low resolution cannot award outstanding ratings, while very expensive sensors with a high resolution can award excellent ratings.) In other words, a facility that is only concerned with keeping an economical cleanliness level may purchase a SLAMbot outfitted with a less sophisticated sensor, while a commercial organization that invests its reputation in the cleanliness rating may opt to equip its SLAMbot with a high-quality air sensor.

“In what manner is the data that is collected by the SLAMbot presented to the staff?” Surveillance data can be delivered instantly to a user terminal over wifi, if the facility permits it. (CSSER, for example, does not.) If not, data can be delivered at the end of a run or it may be extracted manually from onboard flash memory storage (USB or microSD) by staff. Of course, it is preferable that readings are delivered instantly, since if any areas of high pollution are found, all relevant staff should be notified of it immediately.

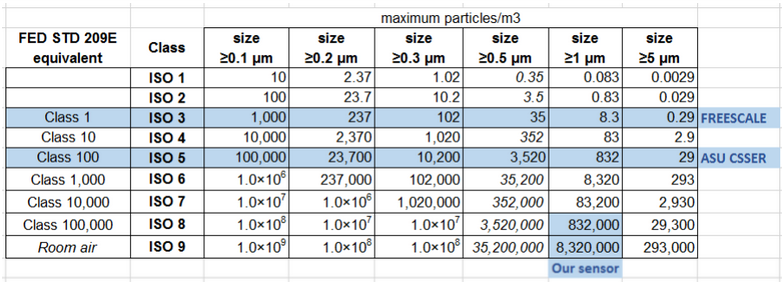

“We need to know how many particles were found of every single size.” MTW was the only facility that expressed this concern, but it’s actually a very understandable one that hadn’t even been thought of yet. The current functional prototype is equipped with a sensor that can only report back how many particles of size 1-um (one micrometer). MTW said they would only be interested in sensing technology that could give a complete profile of their facility, with particle counts for sizes 0.1-um, 0.2-um, 0.3-um, 0.5-um, 1-um, and 5-um. The requirements for a given class rating are very specific, and get more stringent with progressively better ratings:

As mentioned abjove, the SLAMbot’s modular nature means that the facility outfits it the way they want so it meets their needs. If a research facility for example doesn’t need a very impressive cleanliness rating, then they can be expected to outfit their own SLAMbot with a cheap sensor. The cheapest sensors (for example, the one currently equipped) can only report back particle counts for a single size, and have pretty low precision, and certainly cannot be used to issue any kind of clean rating to any reputable facility. That sensor won’t be used in the final product. If a facility (like MTW) wants a full profile of every size, then the appropriate sensor can be equipped.

Looks-like Prototype

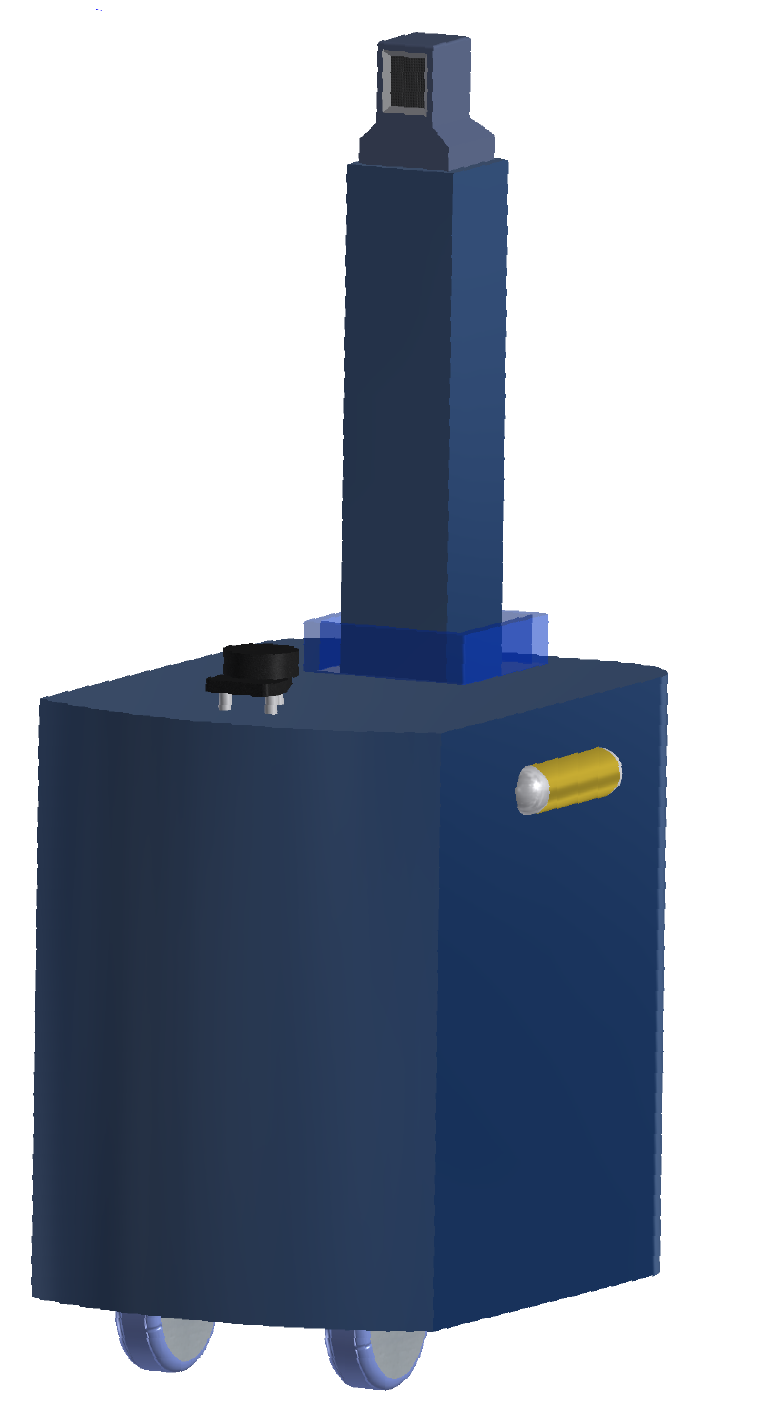

The looks-like prototype was designed in Autodesk Inventor 2015 and is shown to the left. After thoroughly reviewing the concerns and recommendations of cleanroom experts, several concept designs were drafted and fabricated into a 3D model.

Most of the underlying circuitry and electrical components will be sealed away inside the robot’s frame. The parts seen on the exterior are the LIDAR, the air quality sensor itself, and a pair of yellow LEDs to alert nearby staff. The LEDs were decided on after some industry representatives raised concerns over staff being inadequately warned of the robot being nearby. The sizes of many parts were arbitrarily chosen but satisfy the concerns raised by cleanroom representatives.

Most importantly, the 3D looks-like prototype also takes into account the concern of whether particle surveillance will be limited to a single height - the extendable arm can raise the air sensor over twice the height of the robot to monitor air from 2’5” to 7’9”.

All the dimensions (lengths, widths, heights) assigned to the 3D model adhere to the dimensions of the ideal final product. All dimensions of the looks- like prototype were scaled down to 1/10 their original value to reduce printing time and costs.